THE

JOURNAL

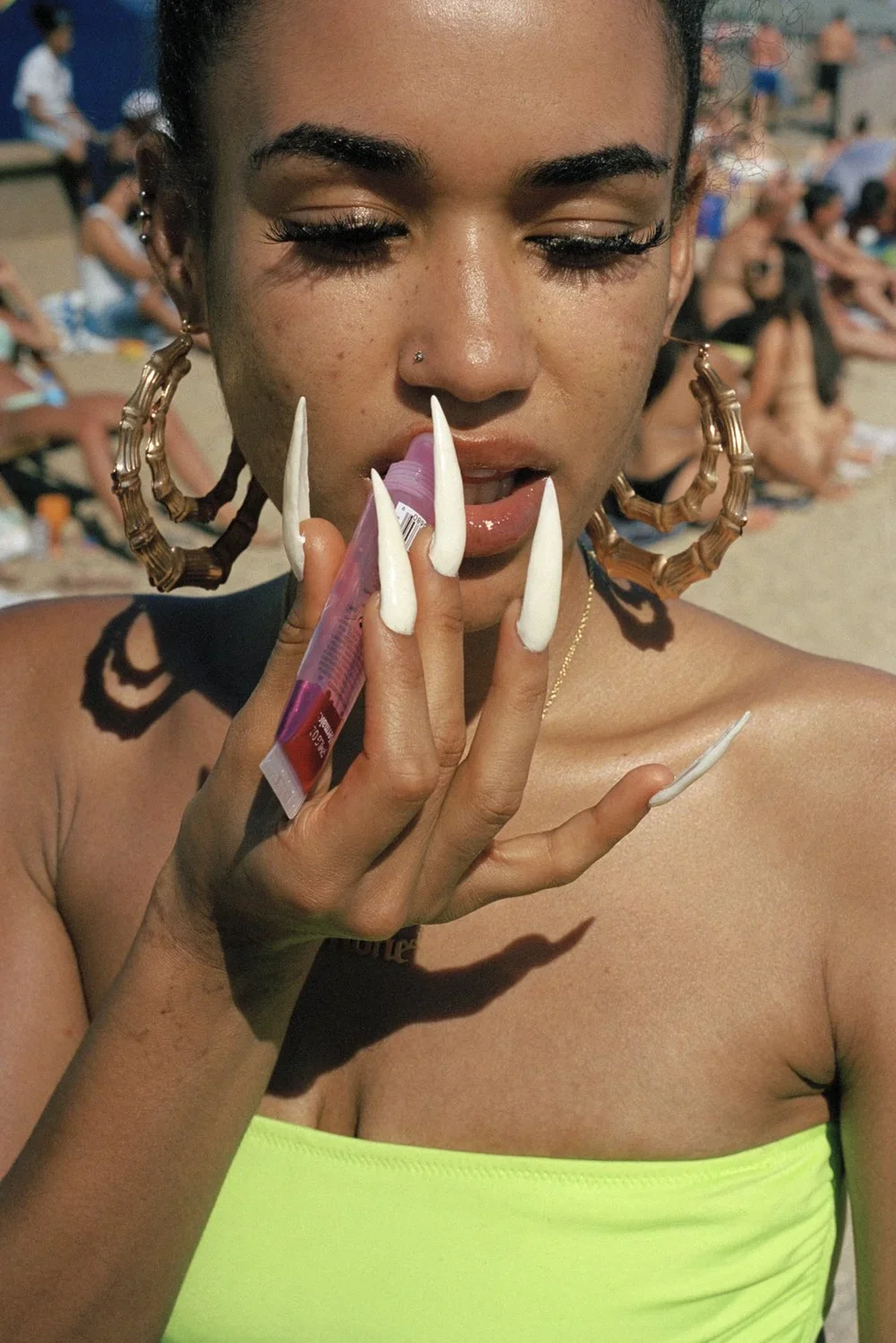

Sophie at the opening of her recent book launch and exhibit in London.

Photo by Teo Della Torre

Sophie Green is not easily boxed in. A London-based British documentary photographer, she has spent over a decade exploring the overlooked corners of British culture, spaces where identity, ritual, and belonging take unexpected forms. Her lens gravitates toward communities that exist at the edges of mainstream narratives, such as Aladura Spiritualist churches (often called ‘white garment churches,’ African-initiated Christian congregations where members worship in white robes), banger racing (a British form of demolition derby), and Traveller gatherings (of the Irish Traveller and Romani communities). In these spaces, she captures the quiet rituals and idiosyncrasies that bind people together.

Known for her bold use of color and graphic detail, Sophie’s images sit between documentary realism and stylized portraiture. Her practice is rooted in collaboration, meeting subjects on equal footing and allowing the work to grow out of trust and time. Many of her projects span years, evolving alongside the communities she photographs.

With three books to her name, including the recently sold-out Tangerine Dreams, and an ever-expanding body of work, Sophie continues to build a visual archive of contemporary Britain — a testament to both the importance of her subjects and the dedication she brings to telling their stories.

What follows is a conversation about the enduring pull of belonging, and what it means to build an archive of modern Britain.

When did you get into photography?

I first discovered photography in sixth form when it was part of my art course, and I felt an immediate connection with the medium. Looking at the work of established photographers, I remember feeling a spark of inspiration I had never experienced before. There was something alluring about photography to me, the way it could capture a transient moment and make it permanent. When I started shooting on film and developing my own prints in the darkroom, I was enchanted by the process. Watching an image slowly emerge on the paper feels like witnessing a small miracle. By sixteen, perhaps a little naive and idealistic, I knew this was what I wanted to dedicate myself to. I went on to apply to study fashion photography at London College of Fashion, where I completed a three year BA.

How do you build trust when working with insular or protective communities?

Building trust with insular or protective communities comes from this sustained presence. I approach every space with humility and respect, listening, observing, and showing up over time. Participation is always voluntary, and I often collaborate with subjects to shape how they are represented. In my project Congregation, for instance, I photographed church congregants multiple times, and through repeated engagement we co-created images that authentically reflected their vision. By demonstrating commitment and care, I hope to show that I am not just an outsider, but someone invested in understanding and reflecting their world.

Time and collaboration are inseparable in my work: the long-term process allows relationships to develop, stories to unfold, and the images themselves to emerge as authentic and empowering reflections of the communities I document.

What first drew you to life at the margins of British culture as your central subject? Was there a moment or encounter that shifted your focus in that direction?

After university, I spent two to three years assisting photographers, working in studios and on shoots, but on weekends I would always take my camera out and shoot independently. I started with street casting and approaching people randomly on the street, but soon I found that encounters often happened by chance simply being out and about, observing, and engaging in conversations would lead to stories. This practice grew out of a desire to explore my own photography. I would leave my front door in London and just go shooting, capturing what was accessible to me at the time.

For example, my project on banger racing began in 2014. I randomly encountered a banger race at Wimbledon Stadium while I was out shooting. By chance, I found my way into the car park pits where the cars were being prepped for the race, and I started photographing the scene as a story. That project has been ongoing for eleven years where I have been returning to banger races and travelling around the UK to document the community, marking my first long-term documentary body of work.

Soon after, my subjects expanded, in 2014 and 2015, I started projects on Travellers, such as Gypsy Gold, attending annual traveller horse fairs to document this aspect of traveller culture. At the same time, I was photographing street car festivals for a project called A Day At The Races, exploring the car modification community. Within a couple of years, these projects were being published in The Sunday Times Magazine, i-D and Dazed, and I began to see a clear theme emerging: British culture, identity, and heritage as lived and celebrated in its diverse, unconventional spaces.

I feel deeply inspired to make work in Britain because it’s such a nuanced and loaded place full of stories. Looking back at my body of work, the trajectory - from chance encounters to long-term projects, feels cohesive and intentional, united by a fascination with British life at the margins.

For example, my project on banger racing began in 2014. I randomly encountered a banger race at Wimbledon Stadium while I was out shooting. By chance, I found my way into the car park pits where the cars were being prepped for the race, and I started photographing the scene as a story. That project has been ongoing for eleven years where I have been returning to banger races and travelling around the UK to document the community, marking my first long-term documentary body of work.

What do you think time offers you as a photographer that immediacy can’t?

Many of my projects evolve over several years, and I’ve found that time offers something immediacy simply cannot: depth. Relationships deepen, trust grows, and the narrative develops in ways that short-term access cannot capture. For example, my banger racing project, returning repeatedly to the races and the communities around them has allowed me to understand the culture, the people, and the stories in a way that would have been impossible in a single encounter.

Do you see your work as preserving culture, interpreting it, or simply reflecting it?

I see my work as playing a small role in all of the above. Photography, for me, is a bridge: it connects people, preserves stories, and celebrates culture. At the same time, I recognise that my work is always a subjective interpretation of the worlds I enter. I choose what to frame, and my photographs are ultimately reflections of what I learn through research, interactions, collaborations, and lived experiences while making the work.

Many of the communities I’ve documented exist on the margins, often excluded from dominant historical narratives. Over the past eleven years, I’ve witnessed both cultural vitality and the quiet threat of erasure, whether among traveller communities or Afro hair salon culture in Peckham, South London. Photography cannot halt these shifts, but it can create a record, a legacy that ensures these stories are seen, valued, and remembered.

There’s often subtle humor in your images. Is that intentional, or something that emerges organically during shooting?

Life is complicated, and I think humour is a survival technique for humanity. When I connect with something humorous, I try to capture it because it reveals the relatability and humanity of the people I photograph. Often these moments emerge organically rather than being planned, but I embrace them because humour can break down barriers between subject and viewer. It creates intimacy, warmth, and a more personal connection. For me, humour is not only a positive emotional state but also a meaningful way to connect with people and places.

Your work is known for its striking use of color and graphic detail. How do these visual elements shape the way a project develops from shooting to editing?

Colour and graphic detail are central to my work, and they come into play both in the field and during editing. When I’m out shooting, I stay alert to how colours interact, how textures and shapes align, and how these elements can evoke feeling or add depth to the story. But just as often, these details reveal themselves later in the edit. Looking at images in sequence helps me notice patterns, contrasts, or visual relationships that weren’t always obvious in the moment, and that process guides me in shaping the rhythm and emphasis of the final narrative.

Has a subject or moment ever completely surprised you—visually or emotionally—during a long-term project?

I feel lucky to have so many surprising, beautiful, and meaningful interactions with the people I meet. While there hasn’t been one single moment, what continually surprises me is the depth of pride people take in their heritage and the strength of their desire for connection. I’m often struck by how much people want to belong to something greater than themselves - a shared identity, a higher purpose, or a collective tradition. That enthusiasm is infectious, and it motivates me. Over the years, I’ve come to see that love, connection, unity, and community form the undercurrent of all the subcultures I’ve documented. Again and again, I’m reminded that, at the heart of it, people are simply looking for belonging.

Your work balances portraiture, still life, and environmental detail. How do these different elements come together to tell a story?

The portraits allow me to connect with individuals and groups, drawing viewers into each world and the communities that shape the cultures I document. Portraits can reveal so much about people through body language, gesture, aesthetics, gaze, and expressions, as well as the environment they are photographed in. They can hint at emotional and psychological states, personal histories, and aspirations, creating points of empathy and understanding.

Alongside this, still lifes and environmental details, often closely cropped, allow me to spotlight elements that hold significance or storytelling power. By isolating a detail through abstraction, I invite the viewer to pause and consider its meaning, to notice the overlooked or the ordinary elevated into something symbolic. Objects, textures, and fragments of environment can serve as clues to relationships, rituals, or cultural identity, complementing the narrative carried by portraiture.

Across portraiture and still life, I can move in close and then pull back out again, offering contrast between the intimate and the expansive. By combining portraits with detailed objects and environmental elements, my work tells stories in layers. It shows both individual people and their communities, and balances intimate moments with the wider context around them.

What do you hope a viewer who’s never stepped into these communities takes away from your work?

The communities I document often embody resilience and relationality. Whether it’s Aladura Spiritualist churches, where rituals and faith provide cultural ties and unity; banger racing, rooted in family tradition and pride; or traveller culture, which thrives on shared codes of conduct, these spaces offer individuals a sense of purpose, belonging, and connection to something larger than themselves.

I hope that viewers who have never stepped into these worlds can appreciate the richness and complexity of these communities. These stories reveal how people celebrate identity, preserve heritage, and create meaningful rituals that anchor them in history and culture. In doing so, they offer lessons in understanding and highlight the importance of connection in an increasingly fragmented society.

Through my work, I aim to challenge clichés of Britishness and showcase a Britain defined by diversity, creativity, and resilience. These communities resist erasure and endure, offering pockets of hope and examples of unity in a world often dominated by division. My long-term documentation is intended as a visual archive that celebrates cultural variety, shared humanity, and the enduring power of belonging.

What was the most challenging project in terms of access, trust, or creative risk? How did you navigate it?

A concrete example of this was my long-term project Congregation, documenting white garment churches and their communities. Access was the first challenge — these spaces are protective and understandably cautious of outsiders. I committed to repeated visits for 3 years, at the beginning without my camera, spending months simply listening, observing, and getting to know people. Over time, trust was built, and I was gradually invited into events and rituals. This allowed me to document moments of intimacy that would have been impossible without those relationships.

At first, my images felt limited. I spent nearly a year shooting only inside the churches during services, but the work remained distant, more reportage than collaborative. It wasn’t appropriate to interrupt prayer or worship, and so I couldn’t yet achieve the intimacy I was seeking. The creative breakthrough came when I began photographing congregants outside, after services. Using church walls and surrounding streets as backdrops, I was finally able to collaborate directly, giving participants space to decide how they wished to be portrayed.

Throughout, I treated subjects as collaborators, photographing many congregants multiple times and returning with prints to share. I also ran photography workshops within the community as a way of giving back. In the end, the project became not only a documentation but a shared creative process and authorship.

Is there a community or project you’re drawn to next, one you haven’t yet explored?

Yes I am working on a large body of new work - its been 4 years already. Sorry I can’t share more. But watch this space!

What advice would you give photographers working outside their own lived experience about documenting sensitive or misunderstood cultures?

I would say start by asking yourself what you feel curious about and find the areas of life or culture that genuinely interest you. Dedicate yourself fully to that work and invest the time needed to understand it. Open up conversations with the people you photograph — listen, learn, and approach their stories with empathy. Documentary work is long-form, investigative, and well-researched, with an ethical and collaborative process involving its participants where stories are explored over time to gain deeper insight. Spend substantial time making the work rather than dipping in and out, and always take copies of the images back to share with the people involved. Be conscious that photographers have a responsibility; your process should be collaborative, respectful, and mindful of the trust placed in you.

For more of Sophie’s work, visit sophiegreenphotography.com